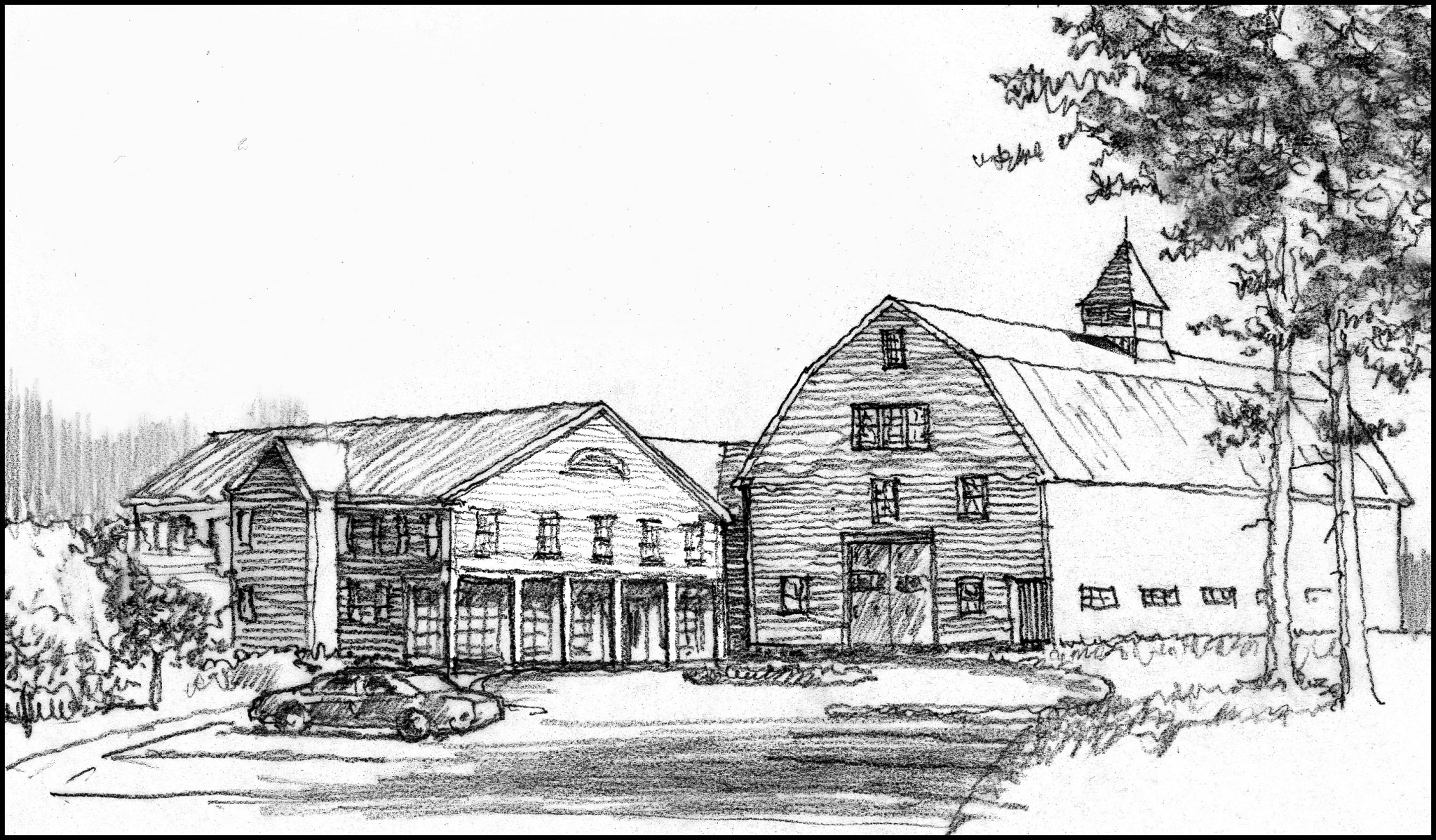

Recently I finished drawing a view of a proposed project and presented it to my clients. The drawing was a mixed-media mélange—some hand sketching, some tricked-up photo collage, some digital painting. The response was classic. “This is great. We can really see it now. This really captures the feeling,” followed by the clincher, “What program did you use to get this?” It reminded me of a question I heard once from a student of mine after I had successfully demonstrated a graphic technique. “What kind of pencil is that?”

I think we all know it’s not the pencil or the software package. A lump of charcoal can produce a picture that draws us in to an idea. So where does this “magic wand” notion come from? I think part of it is wishful thinking. If only I could get the name of that pencil, I could be doing that. Software sales are made on this idea. I tell my beginning drawing students to expect the process to be like learning the violin; you just can’t get to proficiency without first making a lot of scratchy noises.

25 years ago, when I was first called upon to teach drawing, I went to my boss, Joe Esherick and asked him straight out, “How do you teach someone to draw?” He said he didn’t know. “So how did you learn to draw?” He told me he decided one day he needed to know how to draw, so he got himself a notebook and promised himself to draw something in it every day. “I drew anything—I drew my breakfast sometimes…. After a year, I knew how to draw.”

I am concerned about the place of drawing in our current practice of architecture. Maybe I’m just becoming another old curmudgeon, but it seems as though the basic ability to draw is gradually becoming lost to us. What make me think so? Lots of people still have good graphic skills. However, I meet a lot of people coming up in the profession to whom “drawing” means “CADD”. Architecture students and recent grads tell me about what was emphasized at school. Many are not that happy that they didn’t get more drawing instruction—others wonder what all the fuss is about. I also see more people trying to use CADD as a primary (or only!) design tool. I think that is a problem.

So what? Johnny and Jane can’t draw. Well I think it’s a big deal. Giving up drawing would be giving up one of the traditional joys of being an architect. I think being able to express oneself directly with a pencil in a drawing is fundamentally part of who we are and of who we should be as architects. It’s our language, even more than the jargon we sometimes use. We cannot externalize this mental process as some sort of add-on graphics package. Even if such a magic wand existed, I think it would be hurtful to the process.

Even the pursuit of such an option would stem from a vague misunderstanding of what drawing does. As I have said, there are many who equate drawing with drafting and therefore advances in drafting technology as “better drawings.” But drafting represents a very narrow mission. Good drafting is necessary for good architecture, but very far from sufficient. We have all seen technically proficient, even elegant, CADD drawings of really awful or unbuildable designs.

Let’s look at it another way. Let’s take the current design work of Frank Gehry. Only through recent advances in computer aided design could these swirling, free-form compositions be realized. But Frank Gehry is a sculptor, not a CADD guru. His team works out the design in the model, and the whiz-bang computer apps digitize the fully fleshed out shapes. Drafting by itself communicates fully worked out (hopefully) ideas to technically skilled people who are primarily interested in clear and detailed assembly instructions. It has almost nothing to do with how we as humans experience a space.

As opposed to this, drawing can be open ended, not fully defined. Drawing dwells in the realm of ideas. It is part of the interaction with a client, searching for good design solutions. The stray marks we make while sketching can suggest ideas we have not yet made conscious.

When the ability to draw is internalized, it becomes infinitely portable. A pad and a pencil and a client and you have a design process going. It is social interaction. CADD drafting is solitary and thus antisocial—not a forum for developing ideas. Inability to draw is the inability to speak the language of design.

I also think that we as practitioners are partly to blame for this emerging emphasis on computer-only or computer-first drawing. Each of the three architecture schools at which I have taught has felt the pressure from the practicing architects to crank out competent worker bees. And people want jobs; who can blame them? No one starts out as top designer. But school is the time to learn the common language. Becoming a graphically fluent person should not have to be on-the-job training.